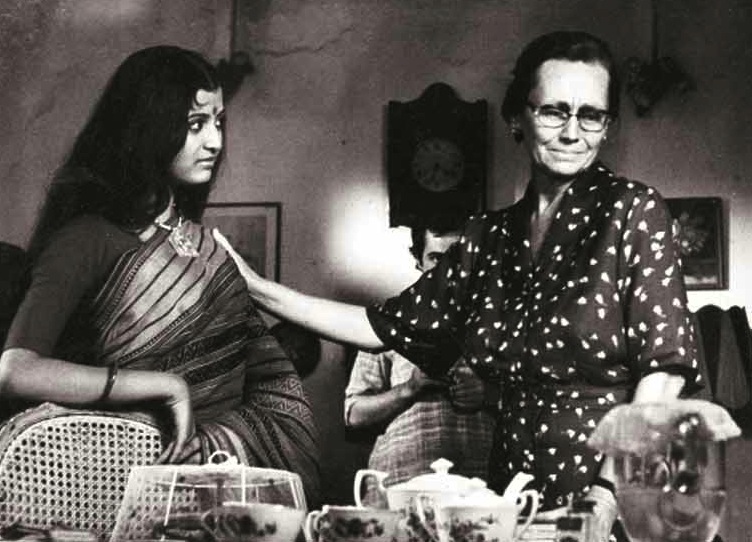

In post-independent India, a teacher, Violet Stoneham (Jennifer Kendal), lives a quiet, lonely and uneventful life at 36 Chowringhee Lane in Kolkata. She teaches Shakespeare despite the lack of interest from her students. When a former student, Nandita (Debashree Roy), pays a visit with her author-boyfriend Samaresh (dhritiman Chatterjee), Violet is delighted, particularly when Samaresh decides that he would like to work on a novel in her apartment. But really Nandita and Samaresh need and use the place to make love. Samaresh admires her gramophone player and she gifts it to him. Samaresh and Nandita get married and move into their own place and no longer need the flat leaving Violet all alone. At Christmas she goes to their house having baked a cake for them where she sees they are having a party and have not bothered to invite her…

36 Chowringhee Lane is one of a handful of Indian films portraying the life and culture of a fast-dwindling minority community, the Anglo-Indians, in India. The text is an engrossing study of the cultural ‘outsider’ – a theme that has received artistic attention all over the world. The faint, distant values of a Western civilization, part of the legacy of colonialism are today wrapped up in one significant tradition – the tradition of the English language. Indian cinema has rarely dealt with people burdened by a dual racial identity. In this sense, 36 Chowringhee Lane is a path breaking film.

Released in 1981, 36 Chowringhee Lane, based on director Aparna Sen’s own story and script, unfolds the story of an ageing and lonely school teacher, Violet Stoneham. She lives alone in an apartment whose postal address defines the title of the film. Her only ‘live’ company is Sir Toby Belch, her black cat. In school, she shares a somewhat warm friendship with Wendy McGowen (Dina Ardeshir), and Rosemary (Soni Razdan), her niece, who later migrates to Australia. Stoneham is an Anglo-Indian, a sub-colonial class the British left behind in India. Much of the film has to do with Stoneham being an Anglo-Indian per se, as much as it has to do with her sense of marginalization in a soil she has grown up to love as her own. It also has to do with her school teaching vocation, where she finds herself isolated and alienated from the mainstream teaching staff, where Anglo-Indian teachers are being replaced by Indian substitutes. The subject that she taught to higher classes – literature – that included Shakespeare – is taken away from her and she is relegated to teaching Grammar to lower classes. The loneliness and the isolation of her single life, dotted by the occasional nightmare, takes an about turn one day. And Stoneham’s life changes forever.

Christmas-to-Christmas is the time frame of the film. It is also a leitmotif. It forms the opening and near-closure of the film’s narrative space. Though the actual time-span of the film covers one year, the narrative is telescopic, moving back and forth into the past, back to the present and into the past again. At times, past and present fuse together. In the closing shots, the visuals are in the present while the soundtrack – letters written by Stoneham to Rosemary in Australia, are in the past. There are forays into a more remote past in the nightmare scene where Stoneham is a young girl betrothed to another Anglo-Indian, James MacKenzie.

Traditions emerge from linguistic foundations. In 36 Chowringhee Lane, one can distinguish a duality: the English language as a fake tradition, and the Bengali (or Indian) language, within which lies the actual psychological compulsions of a people. The ‘outsider’ and the ‘insider’ are thus conjoined within the native land and belong to the Indian culture-framework. This is a new, urban India that cannot shake off an outsider-oriented façade. The tragedy of Miss Stoneham is actually a tragedy of modern Indian society.

In terms of speech patterns and language, Stoneham, Rosemary and Mrs McGowen are ‘outsiders.’ They speak solely in English, using broken and heavy, English-accented Hindi (lobster kitnaa karrke? – Stoneham at the fish market) when they have to. They speak the language of the ‘minority’ – the singsong throw of words is strongly underlined. It is also a ‘colonial’ language that the majority of ‘insiders’ do not much care for, except for the likes of Nandita and Samaresh. A major slice of ‘insiders’ (Hindu Bengalis of Calcutta) do not like to speak in English because (a) many of them (Stoneham’s contemporaries) have not learnt to speak it well, (b) it is a bitter reminder of Independent India’s colonial past. Stoneham has never learnt to speak the language of the ‘insider’ because, though she has lived and worked in Calcutta for a major portion of her life, she does not speak Bengali.

Miss Stoneham’s collection of gramophone records of old English songs is an example of her failure to identify with the Indian-Bengali ‘insider.’ The ‘period’ records – Lipstick on Your Collar, House of Bamboo and Yellow Polka Dot Bikini thrill Samaresh too, underscoring the fact that he takes as much snobbish pride in knowing all about these once-hit numbers as he is of the fact that he writes poetry in English – again – the language of the ‘outsider.’

Though she does not speak of it, Stoneham is desperate for company. She was not aware of this desperation, until Samaresh and Nandita stepped into her monotonous day-to-day routine. When she discovers Nandita and Samaresh kissing, she realizes the true motive of their regular rendezvous, and acknowledges it without comment. There is a touching shot of Miss Stoneham returning from school and fumbling in her purse for the flat key. After a few seconds, she remembers that she has given her key to Samaresh. A lovely smile lights up her face as she rings the doorbell of her own flat. Her way of dressing is strictly Victorian, long, loose, frocks that hide her frame more cleverly than a sari would have. Her terror as she suddenly reads her own future in the smiling, ghostly face of the very old woman at the old age home, are subtle understatements that speak of a hundred little things about the Stoneham woman. She feels guilty when she forgets her Thursday visit to Eddie. Yet, accepts the news of his death when it comes through a telephone call,while she is at school, with quiet calm.

Deep ambers, rusts and browns dominate the environment of Miss Stoneham – her apartment, the home for the aged, to infuse the scenes with signs of a fading present and a nostalgic past, suggesting old age and loneliness. The dim-lit corners of Miss Stoneham’s flat are juxtaposed against the brightly lit luxury of Nandita’s plush bungalow. Ashok Mehta’s brilliant and evocative camerawork gives the lines on Miss Stoneham’s face the right dose of light and shade to add a whole range of expressions and dimension to it – when she is sad, when she wakes up in cold sweat from the nightmare, when she is laughing away at the hypocrisy of Nandita’s marriage rituals (“Oh Dear! After all this time” she says to herself), etc. The carefully orchestrated nightmare sequence appears like a watercolour painting whose colours have gone away. Take the example of Sen’s minute observation of Stoneham’s bathroom in a night scene.

There is a scene showing Stoneham visiting her brother in the old people’s home. Stoneham is frightened by the sight of an old lady climbing up the stairs towards her, as she is about to climb down. The old lady is perfectly harmless but Stoneham is now terrified of anyone who reminds her of old age, disability and death. As the old lady comes closer, her face begins to appear distorted and macabre to Stoneham. With a stifled cry, she rushes past the old lady and disappears around the last bend. One wonders if any other actress, irrespective of talent and commitment, would have been able to ‘live’ the character of Violet Stoneham the way Jennifer Kendal did.

Sen’s attention to minute details of sound, silence, light, darkness and atmosphere enriches the tapestry of the film and reveals facets of the Stoneham character more eloquently than words could have done. Miss Stoneham’s disciplined, missionary upbringing is shown through her use of a letter-opener to open letters. Fading snapshots of Eddie and Rosemary adorn the side table, suggesting memories of another day. Stoneham’s Victorian morals come across when she coyly hides her underwear so Samaresh shouldn’t see them. Her bargaining with the fishmonger in the market to come away with the cheaper variety is an indication of her meagre financial resources. Her obsession with Shakespeare is evident from the name of her pet cat – Sir Toby Belch. Sen reveals her growing emotional involvement with the young lovers through a collage of suggestions – she forgets to visit Eddie on a Thursday because she is busy gallivanting around with Nandita and Samaresh. Rosemary’s letter, once pored over with affection, now flies away in the breeze. A dollop of ice cream falls on one of her students’ exercise books wiping out the name of the girl – Binapani Sarkar – on the label. The interior of Miss Stoneham’s flat spells out the story of its tenant – the upholstery is threadbare, the blackened cooking pans in her tiny kitchenette, that hidden bottle of wine she brings out to celebrate Samaresh’s brand new job, and the gramophone with the old records and the brass horn.

Sen’s first film as director is clearly, a cinema of the cut; she seeks to truncate a particular shot before it yields a definite interpretation in order to create the non-significant image that transforms itself on contact with other images, creating a rhythm where the image or form acts as a substitute for rather than the vehicle of thought. The phonograph serves as a reminder of an age gone by – an age, which, in its sentimental self-articulation, was one of caring, and of respect among the old and the infirm and one in which the young had a greater sense of propriety. It suggests a nostalgic yearning for the past. It’s changed positioning in the two settings – Miss Stoneham’s home and Nandita’s new bungalow – offers a perception of a changing reality in which the old and the new have become irreconcilable. The presence of photographs in Stoneham’s life shows her fondness for memories.

The highlight of 36 Chowringhee Lane lies in Sen’s consistent refusal to co-opt the ‘minority culture’ of Violet Stoneham’s Anglo-Indian identity within the fold of the ‘majority’ and thereby project it as part of mainstream national culture. The identity crisis of Miss Violet Stoneham is resolved within a social context where the rhetoric of humanism, of feelings of brotherhood, of being rooted to the place you were born in, are of prime importance.

The film won several awards in its time like the Best Feature Film at the Cinemanila International Film Festival, Philippines, Best Actress for Jennifer Kendal at the Evening Standard British Film Awards and National Awards for Best Director and Cinematographer among others.

English, Drama, Color