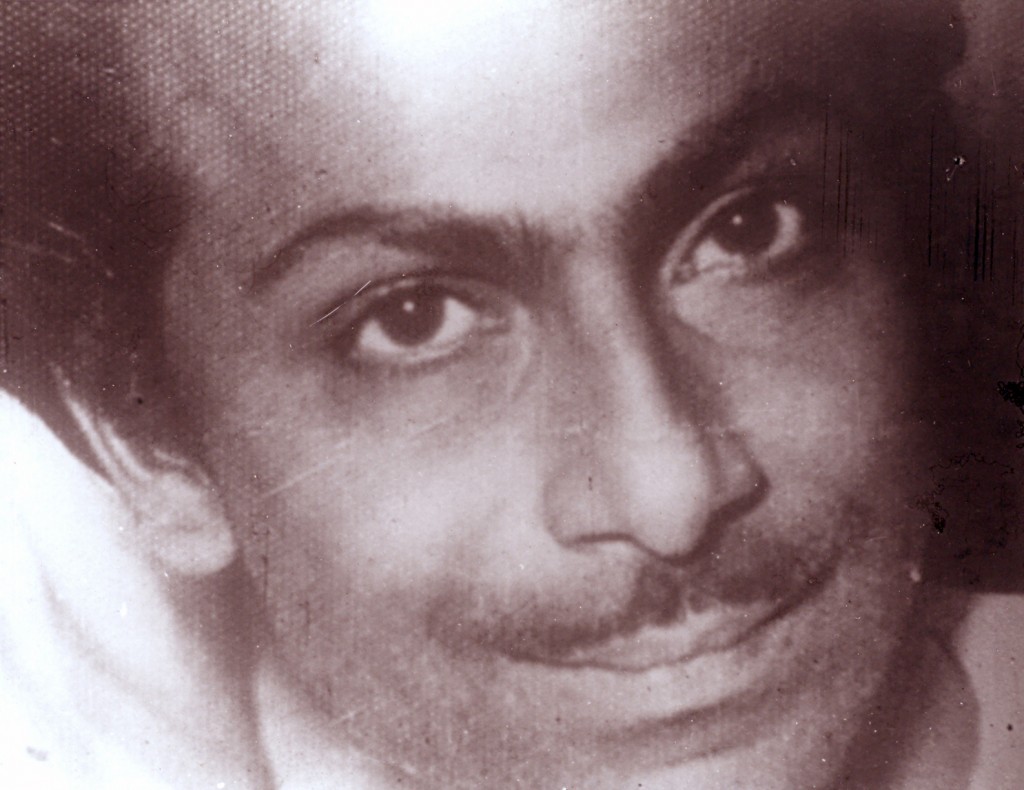

Ages ago, before AR Rahman appeared on the musical map of Indian cinema, before the word ‘fusion’ entered into the vocabulary of Indian music, before Bangla bands turned fusion into a fashion statement within the world of music, these musical genres were already imbibed into, created, merged, and made immortal by the magic wand of one man. His name is Salil Chowdhury, one of the greatest creative poets, lyricists, writers and music composers of all time.

Salil Chowdhury was born on 19th November 1923 (though his year of birth is disputed and often given out as 1925) in a village called Gajipur in 24 Parganas, West Bengal. His love for Western classical music began as a young boy growing up in an Assam tea garden where his father worked as a doctor. His father had inherited a large number of western classical records and a gramophone from a departing Irish doctor. Even as he listened to Mozart, Beethoven, Tchaikovsky, Chopin, etc. everyday, his backdrop was filled with the mystique sounds of nature – the sounds of the forests, the chirping of the birds, the melody of the flute and the folk songs of the region. As a logical extension, he played the flute beautifully and during his revolutionary phase in the freedom struggle, he always carried his flute with him and would begin to play it spontaneously. This musically nourished childhood within an ambience of Nature and Western classical music left a deep and lasting impression of the young Salil Choudhury. He became an excellent self-taught flute player and his favourite composer was Mozart. His compositions often used folk melodies and melodies based on Indian classical ragas but the orchestration was very much western in its construction. He developed a unique style one could identify with easily and get to love at the same time.

Salil’s father, though in the employ of British owners of the tea plantation, would often stage plays with coolies and other low-paid workers of the plantations. This oneness with the workers he saw in his father, this anti-British mindset and deep empathy for the working class influenced the boy Salil, inspiring him and shaping his patriotic passion. As he grew up, he went on to create the school of revolutionary music called Gana Sangeet or Songs of the Masses. His years at Kolkata’s Bangabashi College from where he did his graduation, were the formative years when his clear, unambiguous leanings to the Left moulded and shaped his musical genius.

His friend and close associate Raghu Chakrabarty, a leader of the then-undivided 24 Parganas’ cultural revolution, narrates how financial pressures pushed Salilda to choose music as his vocation in life. Salilda was one among eight brothers and sisters. His father had resigned from his job at the plantations and had migrated to Kolkata. The eldest brother worked in the railways in Lamding. Since by then, this brother had his own family, it was difficult for him to bear the total responsibility of the entire family with his meagre earnings. The father’s retirement benefits were petty. When Salil-da’s father passed away suddenly, it fell upon him to look after the little brothers and sisters who had to be brought up and educated and to bear the medical costs of a bed-ridden mother, besides paying the rent on their house and the costs of day-to-day living of a sprawling family. His father’s sudden and untimely death was a shattering blow. “I was possessed by anti-revolutionary, bourgeousie thoughts at the time,” wrote Salilda about this phase in his life that had forced him to make music his commercial means of living, turning acidic on himself for converting a passion into a commercial proposition. Ironically, this personal tragedy in course of time, evolved into an event of history, leading to the creation of some of the best musical compositions, the creation of a completely new musical genre – gana-sangeet, India has ever known. Salilda’s journey through life is inseparable from his journey through music and looking back, it throws up a classic example of the personal becoming the political and then moving on to merge with the universal. Raghu Chakrabarty says that the contribution of Salil-da’s songs and music at the time was extra-ordinary as it helped to resurrect and revive the Communist Party from total collapse. It paved the way for indirect supporters of the Communist Party to enter into the fray directly.

Living through the Second World War, the Bengal famine and the desperate political situation in the 1940s, he joined IPTA (Indian Peoples Theater Association) and became a member of the communist party. During this period he wrote numerous songs and with IPTA took his songs to the masses. They travelled through the villages and cities in Bengal and his songs became the voice of the masses. They were powerful and stimulating songs of protest, which made people aware of the rampant social injustice that surrounded them. Salilda’s music and lyrics, during his post-Independence, commercial phase in Mumbai, was soaked in and reflected his concern for social injustice. The songs in Do Bigha Zamin (1953) such as Mausam Beeta Jaaye and Hariyala Saawan Dhol Bajata Aaya reflect this mood of protest and rebellion. He called these ‘songs of consciousness and awakening’. Music for him was a strong weapon of revolt, and the lyrics of songs he composed, formed the ‘blood’ for this rebellious music. To know and understand Salil Choudhury, one must know these songs. Since he was a person with strong political convictions and social conscience, his songs rise far above other contemporary composers.

There are two distinct phases in Salil Chowdhury’s life. The first phase, very much non-professional in intent and appearance, started in the pre-independence era of the 1940s and went on till mid ’50s. This was followed by the second phase which was more professional in its content. During the first phase he was a brilliant lyricist, sognwriter, musician and a playwright. In the second phase of his musical creations, Salilda was much more a mature composer than anything else. The composer in him reached a peak in his second phase which began with his migration to Bombay on invitation from Bimal Roy who asked him to write the story and compose the music for Do Bigha Zamin. The story was written in Bengali by Salilda under the title Rickshawala but a Tagore poem of the same title Dui Bigha Jomi was the inspiration for the story. Since Do Bigha Zamin, Salilda composed music for over 75 Hindi films, around 26 Malayalam films and several Bengali, Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Gujarati and Assamese films. He became famous as the most non-conformist composer of the time whose relentless search for perfection towered above everything else.

Salil Chowdhury’s versatility as a music composer unique in style, creativity and expression flourished during his stint with Bimal Roy Films. In Do Bigha Zamin, there is a beautiful lullaby by Lata Mangeshkar, Aaja Re Aaja lip-synched by Meena Kumari in a guest appearance. Juxtaposed against this are the two peasant songs, Hariyala Saawan Dhol Bajata Aaya and Dharti Kahe Pukar Ke, one of which is taken from the Russian Red March, in keeping with the Leftist spirit of the film. Both these songs were in chorus led by the robust baritone of Manna Dey. Do Bigha Zamin remains the best example of Salilda’s mass songs written and composed for the IPTA back in Bengal.

The high point of Biraj Bahu (1954) lies in Salil Chowdhury’s extremely atypical musical score spilling over with different genres of music picked up at random from the heart of a united Bengal. Salilda’s music in Biraj Bahu is different and somewhat reminds one of SD Burman’s style of exploring Bengal’s folk and divine genres. In this film, Salilda breaks away from his regular oeuvre of fusion much before the word came into being, to enrich the film with beautiful Bengali folk songs from Bhatiyali to Keertan. Hemant Kumar’s Mere Man Bhula Bhula Kaahe Dole haunts you much after the film is over.

The music of Madhumati (1958) is a different cup of tea. Each song from Suhana Safar through Aaja Re Pardesi to Zulmi Sang Aankh Ladi, Ghadi Ghadi Mora Dil Dharke, Paapi Bicchua and Toote Hue Khwabon Ne reach far beyond being just a listener’s delight and place them firmly in posterity among the music archive of Hindi cinema. Dil Tadap Tadap Ke, a duet, carries the essence of romance that forms the core of the story. Even Jungle Mein Mor Naacha lip-synched by Johnny Walker in a scene too incongruous for a Bimal Roy film, was a big hit probably because it was the only point of relief in a serious film. When Madhumati was released, Radio Ceylon played seven songs from Madhumati among its top ten. There is no hint of the IPTA and mass songs hangover. Each song defines the characters of the film and their evolution along with the story. This explains Suhana Safar sung by Dilip Kumar when the film opens and he is fascinated by the beauty of the hillscapes when he has not loved and lost and the Toote Hue Khwabon Ne that he sings towards the end of the film. Mukesh sang Suhana Safar, one of his career-bests, and the latter by Mohammed Rafi, sang the former though the character lip-synching the songs is the same.

For the music track of Parakh (1960), Salilda fell back on some of his contemporary Bengali hits sung by Lata Mangeshkar recorded privately. Among these are the immortal numbers O Sajana Barkha Bahar Aayi taken from the Bengali hit Naa Jeyona, and Yeh Bansi Kyon Gaaye was a Hindi transliteration of O Bansi Keno Gaaye. Lata Mangeshkar lists O Sajana among her top ten from the thousands of songs she has sung till date. A playful mood dominates Mila Hai Kisika Jhumka juxtaposed against the somber and serious Mere Man ke Diye. His association with Bimal Roy films marked the future of his music in mainstream Hindi cinema. Take Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Anand (1970) for instance. The four song numbers in the film, three lip-synched by Anand, the doomed protagonist, bring out the pathos of life, and impending death. Maine Tere Liye Hi Saat Rang ke Sapne Chune sung by Mukesh, is an example of how Salilda could bring out the best in one of the most under-rated playback singers in Hindi films. The film itself exemplifies his command over the ambience of a particular scene and the mood of the character singing the song at that given point of time.

Salil Chowdhury is perhaps the first music director to have done the background score without giving the music for the songs of the same film. He could grasp the situation, the storyline and the emotions of a given sequence so well that very often, he created a music track that was distinctively his own irrespective of whether he composed the songs for the same film or not. It began with Bimal Roy’s Devdas (1955) where, though SD Burman composed the music for the songs, Roy asked Salilda to compose the background music. Kanoon (1960), BR Chopra’s film without a single song, had its phenomenal background score done by Salilda. Salilda composed the background music for a large number of Hindi, Malayalam and Tamil films and also for quite a few documentary films for the Films Division of India. Noted playback singer, KJ Yesudas once said, “When Salil and I sat together by the piano and heard his compositions, I was overwhelmed by a divine feeling that his music brought and I have never felt this magnitude of divinity in any other composer’s music.”

Salil Chowdhury is probably the most versatile musician Indian cinema has ever produced. His meticulous attention to detail, a scrupulous ear for musical content, an insatiable desire for improvisation remained with him till the last day. His phenomenal flair for instruments prompted even an expert like Jaikishen to refer to him as a ‘the genius’. Raj Kapoor once said “He can play almost any instrument he lays his hands on, from the tabla to the sarod, from the piano to the piccolo”. He was in fact a composer’s composer, because unlike his market-driven counterparts, he never really set prose to music. To him the melody was sacrosanct and had to precede the words. The situation could then be adapted. In 1962, invited to perform at the International Youth Festival at Helsinki, the late V Balsara recalled how Salilda would spend most of his time composing Bengali songs, then ask his friend Prem Dhawan to translate these in Hindi to be sung by Sudha Malhotra. In the early ’90s Salilda conducted a 50-voice choir for Delhi Doordarshan getting his old comrade Yogesh to translate several of his ‘mass songs’ in Hindi. This programme was highly acclaimed and is often broadcast even now. These mass songs became a part of the independence movement and they are still performed all over Bengal after all these years. They have become an integral part of Bengal’s musical heritage. Salilda’s Bengali songs changed the whole course of modern Bengali music. Bengalis were thrilled and amazed to hear his songs with completely new melodies, new lyrics and totally new musical arrangements. Hridaynath Mangeshkar, who trained in music composition from Salilda for a while, and even Hemant Kumar, who lent voice to hundreds of Salil Choudhury compositions, were so deeply influenced by this genius their own music for films and private recordings, often take one back to the creations of Salil-a. Hemant Kumar’s famous composition Dolkara Dolkara, a fisher-folk song for a Marathi film, sounds like a Salil-da composition.

In the last phase of his life after he migrated to Kolkata, Salilda wrote the lyrics of about 10 Beatles songs in Bengali and recorded them. His second wife Sabita Choudhury and their daughters Antara and Sanchari sang the songs. Those who have heard the songs say that Salilda was totally faithful to the original sheet music. He had said that he found their compositions very interesting. But he went on to add that one should think twice before releasing these songs. They have never been released till date.

He had once said, “I want to create a style that will transcend borders – a genre which is emphatic and polished, but never predictable.” He dabbled in a lot of things and it was his ambition to achieve greatness in everything he did. But at times, his confusion was fairly evident – “I do not know what to opt for: poetry, story writing, orchestration or composing for films. I just try to be creative with what fits the moment and my temperament,” he once told a journalist. He was an outstanding composer, an accomplished and gifted arranger, poet and writer but above all, an intellectual. A master multi-instrumentalist, apart from the flute, he played the esraj, the violin and the piano. He had almost a complete understanding of and knowledge about several other instruments and this is often seen in his musical creation over time. In an interview to The Telegraph (November 21, 1993) Salilda said, “my idea of perfect happiness is my ability to compose a musical note that will unite my countrymen and inspire them to make India among the world’s leading nations.”

Salil Chowdhury passed away in Kolkata on September 5, 1995.